Distinctive attributes of the Stentor roeseli

Gunawardena: Stentor roeseli is a ciliate; this is a clade of single-celled eukaryotic organisms that widely dispersed through most aquatic habitats. The ciliates so named because they have cilia on their cortex, their outer surface. And by moving these cilia they create flow patterns in the water. And, typically, this flow pattern creates a vortex that brings water towards the end of a beautiful trumpet shaped body where there is, in effect, a sort of oral cavity. Now keep in mind, this is single-celled organism. This vortex brings bacterial particles. They’re pretty omnivorous. And we’ve actually observed – and other people have as well – this single-celled organism is capable of capturing a rotifer, which is a multicellular animal, and actually devouring the rotifer. I mean it must be a hell of a meal. It’s a bit like a boa constrictor swallowing a deer. But it’s a voracious kind of predator. They are very diverse. Stentor roeseli is unusually large. You often can literally see them with your naked eye in a good light. They can be as long as a millimeter in extent. Roeseli, as a species, is typically sessile: it tends to anchor itself to kind of debris in the water; algae or something like that. It secretes a kind of mucus-like thing to create a holdfast. So you have to imagine, you know, a kind of frond of algae and this trumpet-shaped organism stuck to the algae by its holdfast. It will pull up its holdfast and sort of swim off. It uses its cilia, then, for locomotion, rather than for feeding. And so, the ciliates were the subject of quite intense study – because of the diversity, and they’re very interesting kind of complexity of their ecological behaviors – in the 19th, 20th centuries. And that’s really where our story begins with the work of Herbert Spencer Jennings on the ciliates.

[ Back to topics ]

Herbert Spencer Jennings

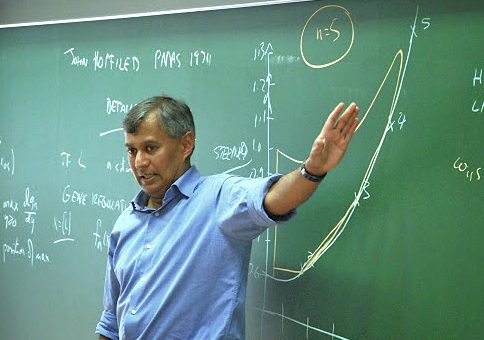

Watkins: The term “gene” was coined in 1905, just a year before the early geneticist, Herbert Spencer Jennings, published a paper that Jeremy and his partners set out to replicate over 100 years later. So we followed up by asking him to tell us more about Jennings and his contributions to science.

Gunawardena: I think has been Herbert Spencer Jennings was one of the great American biologists. His name perhaps has faded from collective memory recently. But in his day, you know, he was a leader in two things, I think, that he’s subsequently being known for. One is his extensive studies of the behavior of what were then called the “lower organisms.” So single-celled eukaryotes and kinds of invertebrate animals and he was part of a very interesting and at times quite ferocious debate that was taking place about the nature of behavior; the nature of life. What’s the origin of consciousness and the complex behaviors that we see in the living world.

And there were to sort of major tracks in this debate. One was that ultimately it was all explainable by sort of physics and chemistry by, you know, sort of simple reflex behaviors. And one of the leaders of this this direction was Jacques Loeb, a German biologist who subsequently came and worked for many years in America. And Loeb is remembered as the kind of originator of these sort of reductionist ideas, which ultimately led to sort of behaviorism and the work of Skinner and Watson and others in in developing a sort of very rigorous, but rather sterile, view of what constitutes behavior. And Jennings was on the other side of the debate and he kept pointing out the fact that the cell is a kind of irreducible agent of life. And it has agency in its own right. And complex behaviors which, certainly at the time, were extremely difficult to explain in terms of this rather simple sort of stimulus-response ideas that were emerging in the debate. And that was what stimulated his work on the lower organisms. So he’s very well known. And when I say it’s “very well-known,” I mean really in a historical sense, rather than in sort of contemporary, you know, kind of collective consciousness.

[ Back to topics ]

How Jeremy got introduced to Stentor roeseli

Leigh: Ryan and I followed up by asking Jeremy when he first learned of the Stentor roeseli and how he became interested in researching them himself.

Gunawardena: I first heard about Stentor roeseli from a lecture that I heard from my friend Dennis Bray in Cambridge who’s a molecular biologist who was a sort of pioneer of the system’s way of thinking about biology … of trying to approach the molecular phenomena we see inside cells from a computational perspective. What kinds of computations are cells carrying out? Dennis was very early to that view. He was giving a talk and he had a slide on this trumpet-shaped organism that I never heard of and this amazing series of experiments that Jennings had performed on it. And I was very struck by this. And I thought, “Really, a single cell is it … it’s capable of doing all that?” I’d … you know, this was completely outside that sort of traditional cell biology that we habitually sort of hear about. And so, I started digging into it now, you know, read Jennings as papers and found that he was a, you know, really wonderful scientist. And I was very excited about this. And then I discovered once I started asking around about so, you know, who followed up with these experiments and what’s the modern story? I was really horrified to discover that among those people who think about these things, the experiments were thought not to be reproducible. So that was really the starting point for our work.

[ Back to topics ]

Jennings’ experiments on Stentor roeseli

Watkins: While an organism as wide as the side-view of paperclip is certainly large enough to see with the naked eye, Doug and I figured they still must be rather difficult to experiment with … especially given the technology available to Jennings in the early 1900s. We asked Jeremy to describe how Jennings’ carried out his experiments into the Stentor roeseli, as well as what it was that he found.

Gunawardena: Jennings’ experiments describe a series of what you might call “avoidance behaviors.” So, what he was doing, he was annoying the ciliate by squirting some carmine dye through a fine pipette at its oral cavity. You know, keep in mind that you know, this was back in 1900. He had very decent optical microscopes and a steady hand, and many years of working with these organisms. So I think he was very skilled at doing this. So what he observed was that the Stentor would go through a series of increasingly elaborate avoidance behaviors. The typical sequence that he described is: they would bend away. So they’re trumpet-shaped and they would just sort flex that to take that oral cavity out of the stream. And if he persisted with the carmine dye stimulation, he noticed – and this takes an acute eye, particular with an optical microscope – he noticed that the cilia around the edge of the trumpet would alter their beating. And the effect of this alteration is to change the vortex in the water; instead of bringing particles towards the oral cavity, it pushes them away from the oral cavity. So it’s sort of spitting, presumably so as not to ingest the carmine particles.

And then, if he kept on persisting by giving these sort of pulses of carmine, the organism would then do a very dramatic action, which is very nice to watch: which is that it contracts extremely quickly onto its holdfast. So it goes from a trumpet sort of flaring out – very beautifully and sort of waving – and then extremely quickly it collapses down onto its holdfast. The cortex of the ciliate – the structure around the plasma membrane – is a very elaborate structure. It has ionic and mechanical properties. And it’s a bit like a muscle, and it contracts very sharply. And so, if you don’t do anything, you know, it stays sort of hunkered down in this contractor state. And then, much more slowly, it sort of elongates back to its normal shape and starts its feeding behavior again. And then Jennings would again stimulate it with the carmine pulse. And now it wouldn’t go through the bending and ciliary alteration, it would contract. So, its behavior changes to this contraction behavior. And if you kept on stimulating it it would go through these contractions some number of times. And then, finally, it would get, you know, totally fed up and pull up its holdfast and swim off. So those were the four behaviors – bending, ciliary alteration, contraction, and then detachment – that Jennings described. And the way he described it there was this hierarchy: bending, ciliary alteration, contractions, detachment.

[ Back to topics ]

Botched replications of Jennings’ experiments

Leigh: Jennings’ observation that these four avoidance behaviors existed in a neat order of ranked preference suggested that the Stentor roeseli were making relatively complex decision-making calculations … something that fascinated Jeremy. But later he learned that an attempt made by two researchers from the University of Nebraska in the 1960s failed to replicate Jennings’ findings. This bothered him, so Jeremy set out to unravel what might be responsible for this discrepancy, as he explains next.

Gunawardena: I was in touch with some of the people who had done more recent – sort of 70s, 80s – studies on single-celled organisms. And I got information about this paper where Reynierse and Walsh had tried to reproduce Jennings’ experiments, and they weren’t able to and nobody believed that the experiments were correct. And, as I discovered subsequently, there was a sort of backstory there. So, one of the successes, I suppose, of behaviorism was that it managed to identify and define particular forms of learning which became the basis for, you know, sort of very carefully conducted experimental studies of those kinds of learning behaviors. Some of these are very familiar. There’s Pavlov‘s famous work on conditioning. There’s also Skinner’s work on instrumental learning – or trial-and-error learning – and you know, many people, I think, have seen Skinner’s pigeons playing ping pong through this kind of trial-and-error learning. The experiments by Reynierse and Walsh were conducted at the time of those kinds of developments and they interpreted Jennings’ work as showing some form of associative conditioning of those organisms. And they tried to repeat the experiments from that standpoint. Now, I think Jennings certainly didn’t think about conditioning. And there are not two stimuli involved which are the basic form of conditioning experiments. It’s an association between two stimuli. And Jennings only had one stimulus. So this this whole starting point for Reynierse and Walsh was sort of wrong. And it’s interesting why it was that the context they were working and led them to take this view? But the really bizarre thing about it is this …

Watkins: We’ll hear just what it is, after this short break.

ad: Altmetric‘s podcast, available on Soundcloud, Apple Podcasts & Google Podcasts

Watkins: Here again is Jeremy Gunawardena.

[ Back to topics ]

Missteps in the replication

Gunawardena: This I only discovered when I – well, I couldn’t find this article because it wasn’t electronically available. So I actually had to do the unusual thing of going to the library. And digging through the stacks. And it was many years since I’d had the opportunity to do that. So it was almost like a Dickensian experience. And I uncover, you know, this paper and photocopy it, and started reading it, and discovered that they were unable to obtain Stentor roeseli. And therefore decided that they would just pick the nearest Stentor, which was Stentor coeruleus, which is very readily available. You can get it from biological supply companies. The only problem is that Stentor coeruleus is typically not sessile, it’s motile. And as they point out out in their paper, when they tried to do these proddings … stimuli … to reproduce Jennings’ experiment, the organism, as they put it, “swam away.” And so it’s really laughable reading this paper and saying, “Seriously, this is an attempt to reproduce Jennings is experiments?” It was ridiculous.

But the final kind of paradox is that somehow this very bad paper managed to persuade everybody in the field that Jennings was wrong. And so, it raises the question: what was it going on in people’s minds at the time that they didn’t want to believe Jennings? And any piece of evidence – even this kind of nonsense that this paper had put forward, you know, really shoddily undertaken experiment – was sufficient to convince them that this was the case, and establish the fact that the Jennings was wrong. And I think the answer, partly – and I’m, you know, I’m not a historian – so I’m just guessing here – is that this became part of a larger debate on whether single-celled organisms could exhibit associative learning in the behaviorist paradigm. And associative learning is the more complicated form of learning which really suggests a sort of significant learning capacity. It’s very much more elaborate than, sort of, non-associative learning. And this Reynierse and Walshs’ study of Jennings’ experiment was interpreted within this conditioning paradigm. And that was part of establishing this consensus that single-celled organisms can’t learn in an associative fashion.

[ Back to topics ]

The analysis of Jeremy’s replication of Jennings

Leigh: After months of practice handling the Stentor roeseli, Jeremy and his team felt ready to carry out their own replication to see if the organism could really exhibit a hierarchy of behavioral responses or not. Ryan and I were interested in learning more about how they carried out their analyses and what it was that they found.

Gunawardena: To begin with, I think we had a very qualitative view of saying well, you know, if you look at this, it looks as if this is happening. It took a while to get to the point where we could make a more precise statistical statement, and I think ultimately it was quite straightforward. There was nothing complicated about it, but it takes longer to think about these things than one might imagine, in retrospect. And the idea was that we do an experiment on the Stentor, and it involves these pulses of stimulation, and these behaviors. We try to define the behaviors as carefully as we could in such a way that if you looked at the video, so we had a … you know, it’s video microscopy. We have a quite long and good quality video of this process. So we try to define the behaviors quite clearly so that we could say, “This series of frames that you see at this point in time constitutes …,” you know, a bending or a cilia alteration or whatever. And from that we could abstract what we were seeing into a sequence of behaviors. So we gave little code letters to each of the behaviors, and we can write down a sequence. So that step of, you know, going from an experiment and video, to essentially a mathematical entity – it’s a string of letters as a description – that was a very important sort of clarification of what we had.

And then the question is, “What can you say from these sequences?” And what we realized is that although each sequence is very different – some are very long, some short, depending on the number of contractions; number of other behaviors that we see – they don’t all show … by any means, there’s in fact very few that show that this behavior hierarchy. But you can ask the question: does alteration and bending happened before contraction or after contraction? But, I should perhaps just explain that it’s quite hard in our videos to distinguish the timing of ciliary alteration in bending. They often happen sort of more or less at the same time. So we made the decision that we wouldn’t attempt to sequence those. We would always treat them as together – as alteration or bending – and treat that as a unit. And so, if you were to assume that there’s really no relationship between these things as a null hypothesis – so if alteration bending and contraction were happening independently of each other – then we would expect to see, in any sequence, the order A or B followed by C as often as we would see the other order. And it’s very easy to do the statistics. It’s a binomial distribution to work out what the expected frequency would be of a particular order, and then to ask question, “Well, is that the frequency that we actually see?” And what we see is that actually when you look at the distribution, the frequency that we actually see is several standard deviations away from where it would be expected to be on the null hypothesis. And that was the basis for making the claim that there is in fact a specific order. It’s not that it … we always see it, but we see it so often that it would not be reasonable to explain it on the behavior that there isn’t an order.

[ Back to topics ]

Jennings’ findings replicated, and new findings as well

Watkins: Jeremy and his partners found that the Stentor roeseli carried out the behaviors in a non-random order, just as Jennings reported: first, they were more likely to give up and detach from their holdfast only after first altering their cilia … or bending away. And secondly, they found that this alteration, or bending, was more likely to happen before contraction than after it. But, curiously, Jeremy found that the likelihood that the Stentor roeseli would either contract – or detach – were as random as a coin toss, as he explains next.

Gunawardena: I think intriguing thing about this is, you know, how are they doing this? Because it’s … it’s actually really tricky to get, you know, pure randomness, and a fair coin tosses is purely random as you can get. And here, the thing that to me remains extremely puzzling is: it’s a single cell and all of this behavior and, you know, elaborate sort of phenotype is orchestrated by molecules bumping into each other. And we know that that’s you know, extremely stochastic process that is under the hood. So it’s not surprising that it’s stochastic. What’s surprising is that it’s purely random; that the probability is, you know, a half. How on Earth from pure stochasticity does the organism or evolution find a way to get a probability that’s so close to a half? That is really puzzling. And when we do it, we toss a coin. But the reason that’s half and half actually relies on very careful machining of that coin so that it it’s uniform. And so that when you, you know, slip your finger and toss it into the air, the influence of the initial conditions is kind of wiped out. And if there was a tiny imbalance it would it would show itself in something that’s not quite 50%. So that randomness, like a random number generator, requires lot of care to be really random. So how does on Earth this happening in Stentor? I’ve no idea. I couldn’t write down a molecular mechanism. I mean, we study these things and it’s easy to write down stochastic mechanisms because they’re always stochastic. But trying to get them to produce 50% is not something I know how to do.

[ Back to topics ]

Can single-celled organisms think?

Leigh: While anyone who owns a dog or cat will tell you that, “Yes, of course non-humans can also think,” the further you stray from mammals, the more dubious this claim becomes. Nevertheless, the Stentor roeseli certainly seem to exhibit some form of learning, which implies that they also experience cognition … and, for any creature, that possibility opens up questions about consciousness, free will, and choice. So we asked Jeremy his thoughts … on just what counts … as thinking.

Gunawardena: We kind of wandered into this little bit like innocents in the wood, because what we study in the lab is sort of information processing in cells. We don’t work on ciliates. We don’t work on learning. It took us a while, and it was probably really only during the review of the paper that some of these issues really came out. So, this whole question of what is learning is a minefield. Even finding a definition that everyone accepts is difficult. But, I think a reasonable definition of learning is the ability to take information from the environment and make a persistent change to behavior, even if the information subsequently goes away. And that’s a very broad and very sort of loosey-goosey kind of statement. But I think that would get some consensus as a reasonable definition of what learning constitutes.

In the context of, say, developmental biology – which is a very different context, but I think has interesting analogies here – we often use the phrase “decision-making.” You know, cells as they’re going about the of building the organism: you have a cell, it receives some cue from its environment typically a chemical signal but perhaps mechanical or something else. And this cue leads it to make a decision that it’s going to follow a particular trajectory – a lineage trajectory – and become, say, a nerve cell ultimately. Having made that decision, it retains that knowledge and persists in that lineage despite fact that the cue goes away. So, on the basis of the very broad definition, one would treat that as – I would say – a form of learning. But I think that actually tends to cause problems for people who study learning, because they tend to think of those kinds of decisions as being quote-unquote programmed rather than being “truly learning.” And this is where it gets very difficult for us to sort of parse what’s real learning versus what’s not real learning. I personally think that decision making is a particular form of learning, just as non-associative learning; say, habituation is also, in the learning literature, is regarded as a simple form of learning: you receive the same stimulus and your response becomes weaker and weaker and weaker. Here, in the case of Jennings’ experiment, he gives the same stimulus to the organism and it does something different. It changes its mind, as we put it. It decides to do something different. So I would regard that as form of learning, but we carefully removed the use that word from the paper.

[ Back to topics ]

Implications of single-celled decision making

Watkins: Though published in the journal Current Biology, Jeremy and his team’s paper touches on various other fields, including history, mathematics, and cognitive science. And [it] even has implications for philosophy and consciousness. So we ended our conversation by asking him what it was that led him, as a mathematician, to gravitate towards looking at biology in these counterintuitive ways.

Gunawardena: As a mathematician, I was educated in the British mathematical tradition, and it’s very down-to-earth. And it regards issues of history and philosophy as being sort of Continental European perversions. I mean, I’m caricaturing things, but broadly speaking that was the attitude. And history was definitely one of the most boring subjects I dealt with it school. It was all dates and, you know, it meant nothing, really, at the time. And so, my interest in history and also philosophy was really provoked by coming to biology. And I never really thought about them seriously before then. And what I came to realize in biology is that it’s often impossible for an outsider … you know, somebody who hasn’t gone through the traditional apprenticeship of, you know, undergraduate/PhD stuff. If you come to the subject from outside, many aspects of it it are really mysterious. And I began to understand this when I started teaching, particularly, because that’s when you you know, you stand up in front of a class. You have to say something, and then you think, “Is that really correct?” And that’s what provokes this attempt to unpeel the layers. And I found I just couldn’t understand what was going on now – and why was that people were doing and saying the things they were doing and saying now – without going back, and sort of uncovering where do these ideas start? And how is it that they’ve come to take the form they have now? So that historical dimension, it just sort of [has] grown. And I see for me personally. I find that extremely important. I couldn’t do science without thinking that way.

[ Back to topics ]

Links to article, bonus audio and other materials

Watkins: That was Jeremy Gunawardena discussing his article “A complex hierarchy of avoidance behaviors in a single-cell eukaryote,“ which he published with Joseph Dexter and Sudhakaran Prabakaran in Current Biology on December 16, 2019. You’ll find a link to their paper at parsingscience.org/e70, along with transcripts, bonus audio clips, and other materials we discussed during the episode.

Leigh: About those bonus audio clips. A week ago, most of us never used the term “social distancing”, but this is our new reality for the time being. So, while it’s not a big thing, all Bonus Clips are available at parsingscience.org … regardless of if you’re a donor to the show or not. We hope this helps brighten your days a little. Stay safe, everyone.

[ Back to topics ]

Preview of next episode

Watkins: Next time, in episode 71 of Parsing Science, we’ll be joined by Veronica Sevillano from the department of Social and Methodology Psychology at the Autonomous University of Madrid. She’ll discuss her research into our social perceptions of animals, and how she’s applying intergroup relations theory to understanding why we adore some animals … but despise others.

Sevilla: In the same way that we hold stereotypes about social groups, immigrants, or women, or whatever … we also do for animals. And our stereotypes about animal species have an impact on how we feel, and how we behave toward distinct animals.

Watkins: We hope that you will join us again.

[ Back to topics ]

Next time, in episode 71 of Parsing Science, we’ll be joined by Verónica Sevillano from the department of Social and Methodology Psychology at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. She'll discuss her research into our social perceptions of animals, and how she's applying intergroup relations theory to understanding why we adore some animals, but despise others.@rwatkins says:

Though published in the journal Current Biology, Jeremy and his team's paper touches on various other fields, including history, mathematics, and cognitive science ... and even has implications for philosophy and consciousness. So we ended our conversation by asking him what it was that led him - as a mathematician - to gravitate towards looking at biology in these counterintuitive ways.@rwatkins says:

While anyone who owns a dog or cat will tell you that “yes, of course non-humans can also think,” the further you stray from mammals, the more dubious this claim becomes. Nevertheless, the Stentor roeseli certainly seem to exhibit some form of learning, which implies that they also experience cognition ... and - for any creature - that possibility opens up questions about consciousness, free will, and choice. So we asked Jeremy his thoughts ... on just what counts ... as thinking.@rwatkins says:

Jeremy and his partners found that the Stentor roeseli carried out the behaviors in a non-random order, just as Jennings reported: first, they were more likely to give up and detach from their holdfast only after first altering their cilia … or bending away. And secondly, they found that this alteration … or bending was more likely to happen before contraction than after it. But, curiously, Jeremy found that the likelihood that the Stentor roeseli would either contract - or detach - were as random as a coin toss, as he explains next.@rwatkins says:

After months of practice handling the Stentor roeseli, Jeremy and his team felt ready to carry out their own replication to see if the organism could really exhibit a hierarchy of behavioral responses or not. Ryan and I were interested in learning more about how they carried out their analyses and what it was that they found.@rwatkins says:

We'll hear just what it is, after this short break.@rwatkins says:

Jennings' observation that these four avoidance behaviors existed in a neat order of ranked preference suggested that the Stentor roeseli were making relatively complex decision-making calculations ... something that fascinated Jeremy. But later he learned that an attempt made by two researchers from the University of Nebraska in the 1960s failed to replicate Jennings' findings. This bothered him, so Jeremy set out to unravel what might be responsible for this discrepancy, as he explains next.@rwatkins says:

While an organism as wide as the side-view of paperclip is certainly large enough to see with the naked eye, Doug and I figured they still must be rather difficult to experiment with ... especially given the technology available to Jennings in the early 1900s. We asked Jeremy to describe how Jennings' carried out his experiment into the Stentor roeseli, as well as what it was that he found.@rwatkins says:

Ryan and I followed up by asking Jeremy when he first learned of the Stentor roeseli and how he became interested in researching them himself.@rwatkins says:

The term "gene" was coined in 1905, just a year before the early geneticist, Herbert Spencer Jennings, published a paper that Jeremy and his partners set out to replicate over 100 years later. So we followed up by asking him to tell us more about Jennings and his contributions to science.@rwatkins says:

The single-celled organism that Jeremy and his team experimented with is called Stentor roeseli. As neither Ryan nor I had previously heard of them, we started out by asking Jeremy to tell us more about what they're like, and what's so striking about their behavior.